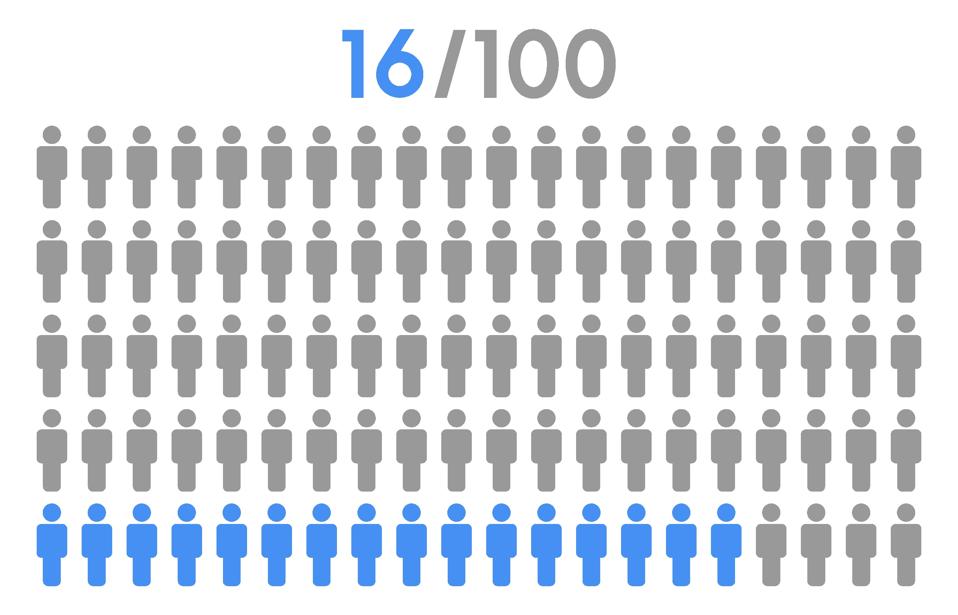

Only 16 percent of corporate innovations succeed at generating revenue at scale, according to research from the consulting firm Change Logic.

getty

Corporate venture capital is an attractive way for firms to play, but it does not help innovation go to scale

Depending on how you define success, Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) is either a brilliant technique for funding innovation from the balance sheet or an expensive distraction from the hard work of building new ventures. My answer is that it is both an enabler to innovation and a potential distraction that keeps firms trapped in the safe space of ideas and concepts.

In a new episode of the Inside CVC podcast, I had an opportunity to expand on this view. The show’s hosts, Steve Schmith and Philipp Willigmann, led a provocative conversation that got me thinking more about CVC and its role in corporate innovation.

Corporate venture capital is a driver of the sixteen percent problem

Corporate venture capital is when a corporation invests in a startup. Some companies do this to generate a financial return. They reckon they can combine the company’s capital with knowledge of a market segment to pick good investments. Other firms want to build closer relationships with firms that might give them “headlights” into future technologies or business models or even be acquisition targets.

My assessment is that these investments are a symptom of corporate innovation failure. Investing in a startup does not guarantee access to its innovations. It is just a low-risk way of participating in innovation, that makes little difference to corporate performance. This article is a summary of my main argument.

My main argument is that CVC is part of the problem that drives underperformance of corporate innovation. At best, only sixteen percent of corporate innovation converts into scaled ventures (see more on this in my article with Christine Griffin in Sloan Management Review). When it succeeds, it is typically because the corporations involved combine assets from the existing business with those they acquire, build, or access through partnerships.

When it fails, it is because firms mistake innovation for “invention” or “ideation.” They get excited by ideas and possibilities, rather than the hard slog of incubating and scaling new technologies and business models. Although corporations possess assets and resources that they could use to drive innovation tend not to do so.

Corporate venture capital is lower risk than true corporate innovation

The failure to leverage internal assets stems from a fear of disrupting existing operations or antagonizing powerful stakeholders. It is much easier to go outside and discover without constraints, even if it is someone else doing the work. I call these factors the “silent killers of innovation.”

However, this is not the only way CVC lets companies play safe. Corporate venture capital investments are made from a company’s balance sheet. The money comes from the profits the company makes and, because it is an investment, it stays on the balance sheet as an asset.

Compare this to an investment in developing new technologies or building a new capability to sell in new markets. These investments count as an operating expense. That means that they eat into the quarterly profits reported to investors, depressing key metrics like earnings per share. These are the metrics that drive stock prices and executive bonuses.

This difference makes a CVC a much more attractive bet than investments in business building. Investing from the balance sheet has limits, but fewer downsides, and, if well managed, may even generate a return to boost the company’s earnings. Whereas, investing from the operating expense creates immediate short-term pressure to demonstrate results.

The net effect is for CVC to reinforce a corporation’s reluctance to innovate. They can play with innovation without putting anything that they care about at risk. As a result, they deny themselves the benefits of using the very assets that could make difference.

Corporate venture capital is a financial illusion

This difference between investing from the balance sheet and operating expenses plays out in how some corporate managers think about internal versus external innovation investments. Building a new business is risky. Uncertainty is high and it is easy to waste resources on unproven concepts. When there is an option to deploy the same resources to boost revenues in the existing product lines, then most managers will take it. It is rationale to choose safe returns over uncertain ones.

This has a negative long-term effect on the company, as it contributes to lower growth rates, losing market share to new entrants, and the host of other problems that I describe elsewhere. The alternative is to learn to manage these risks systematically, so increasing the likelihood of success.

Capital investments – be they acquisitions or CVC – receive much less scrutiny. These investments convert into balance sheet assets that in the short term do not reduce the value of the firm. The case for such investments are based on “projected returns” for the startup involved. This reduces the perception of personal risk. They may be held accountable for delivering the business case, but not for years to come.

They operate from a belief that external ventures automatically offer better returns than internal projects. This is despite evidence that startups have an even higher failure rate than corporate ventures and evidence that venture capital rarely outperforms the financial markets.

Corporate venture capital and scaling innovation

The evidence that CVC contributes to corporate innovation outcomes is strong, but lopsided. The bias is all on the “ideation” discipline of innovation, it tends to ignore incubation, and, most especially, scaling. Academic studies often quote impacts like high patent registration or intangible benefits like knowledge absorption. These benefits matter, but they at best loosely correlated with converting innovation into revenue.

A corporate’s primary innovation advantage is that they have assets for scaling innovation. That is why corporations acquire startups. Established companies have the sales channels, customers, manufacturing plants, product management disciplines, technical capabilities, needed to turn a startup’s concept into a revenue generating business.

The firms that succeed at building new businesses – IBM’s Emerging Business Opportunities of the early 2000s, LexisNexis’s Risk Solutions business, AGC’s expansion into Life Sciences, to name just a few – are good at combining assets. They build new assets, buy new ones, partner for some, and leverage what they have already got. This is the secret sauce of corporate innovation and the reason that my book is subtitled: “How corporations beat startups at the innovation game.”

CVC should be another route for getting access to these assets. It can bring insights into the acquisitions a firm might make. It can also alert them to the emergence of new businesses models.

Corporate venture capital has an organizational problem

CVC investment portfolios can be engines of new market insight and innovate growth for corporations, but most often they are not. There is an organizational wall around CVC, that prevents an integration of the CVC strategy, with that of the business. It reports to the finance function or perhaps the team responsible for mergers and acquisitions. This makes the CVC team a disconnected appendage in organization, driving financial returns, but limited strategic value.

It is important to break down these walls because insight from investing in startups does not come from attending occasional board meetings. It requires sustained immersion in customer problems the startup addresses and the mechanisms they use to evolve innovative solutions.

There are numerous cases where corporations have invested in startups without any real plan for integrating the assets into a plan for growth. These deals frequently result in failed acquisitions, wasted capital, and missed opportunity to build new competencies. When CVC succeeds it is because there is a tight alignment between the teams working to make the investments and those seeking to create new ventures.

Corporate venture capital can enable an innovation agenda. It just cannot sidestep the long, hard road of incubating and scaling a new business. It may look like it is low risk, but in reality, it risks being low return.